Limited Edition Information

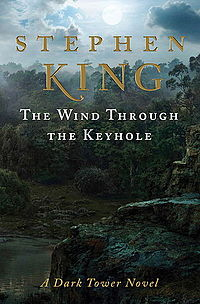

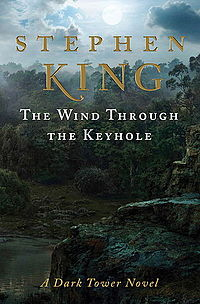

| The Wind Through the Keyhole |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

Limited Edition Information |

In The Wind Through the Keyhole, Stephen King once again returns to the myth-pool that has shaped and to some degree defined his entire career. Readers may wonder if it’s one time too many; after all, the finale of the series proper in 2004 was met with some controversy, and the way that the edges of the story keep encroaching in later fiction – as in The Colorado Kid and “Ur” – have given some readers Tower Fatigue. But time and distance away from the main narrative have given King some perspective on his epic tale. Keyhole is meant to function as a Major Arcana Dark Tower novel, sequenced between Wizard & Glass and Wolves of the Calla (has anyone noticed that the Dark Tower books have a serious “W” fetish?). The fear with an interstitial – or “midquel” – book is that it can potentially feel too constrained, its storytelling hampered by the need to connect the events before and after. Keyhole, contrarily, feels fresh and wide-open, attaining its own unique flavor among the Tower books while meshing seamlessly with the fabric of the series. Most importantly, it manages to retain the quest structure of the first four novels and also subtly underscores King’s obsession with the nature of fiction in the latter books, providing a necessary bridge between the two halves of the series. That actually may be the most apt word to describe The Wind Though the Keyhole: necessary.

The next best word to describe this book? Fun. Veritable buckets of it.

The Wind Through the Keyhole is structured similarly to Wizard & Glass: we begin and end with the ongoing quest of our adventurers – Roland, Susannah, Eddie, Jake, and Oy – with a long middle section that gives way to storytelling. We’re treated to another one of Mid-World’s terrific portmanteaus: this book’s chilling “starkblast” now anticipates Wolves of the Calla’s “beamquake.” There’s not much in the way of character development or growth – midquels make such things almost impossible – but Jake’s transformation from child to expert gunslinger is given more page time, showing him growing up more and ranging about on his own. The ultimate fate of these characters in The Dark Tower notwithstanding, it’s wonderful to reconnect with them here, in the prime of their journey.

As with Wizard & Glass, we get a new peek into Roland’s past (not as deeply this time out, but that’s fine), but we also hear what amounts to a Gilead fairy tale. “These tales nest inside each other,” Roland says near the beginning of the Keyhole, and that’s one of the book’s primary pleasures. The deeper we go into The Wind Through the Keyhole, the larger and more interesting Roland’s world seems. We are told throughout the series that “the world has moved on,” but Keyhole gives us a fascinating extended look at what it moved on from.

Roland’s new tale of his past is told, intriguingly, from the first person point of view. King’s grown more comfortable with this style lately, using it to achieve heightened emotional resonance in novels like Bag of Bones, Duma Key, and 11/22/63. It’s a seemingly minor story when compared with Roland’s long tale of his tragic first love and his bewitched matricide in Wizard & Glass, but it’s no less entertaining. Months after Roland’s mother’s death, his father sends him and his friend Jamie DeCurry to a small town called Debaria to investigate a “skin-man,” a shapeshifter who has been slaughtering the townsfolk. Despite the macabre goings-on, this section of Keyhole is written with a light, deft hand: it’s King in familiar territory that he still finds compelling. The investigation is compelling enough (including fascinating, seemingly deliberate homages to King’s early book, Cycle of the Werewolf – a child’s severed head on a post recalls the pig’s head in the earlier book, and the identity of the skin-man relies on the man’s particular disfigurement – as well as some interesting echoes of Desperation) but it’s almost beside the point. World-building and character-building are far more important here. Debaria is an interesting place, different enough from either Delain or Mejis so that this past world feels real, lived-in, and expansive. While the investigation itself is fairly routine, Roland’s approach to it reveals more about him. This crucial time following the deaths of his lover and his mother have toughened him, but he’s still not yet the reserved and obsessed man we meet at the start of The Gunslinger. We see glimpses of him as the professional gunslinger he’ll become, the ambassador/paladin we’ve seen at River Crossing in The Waste Lands and in Calla Bryn Sturgis in Wolves of the Calla. We also see Roland struggling with the concept of being forgiven, as we saw in Wizard & Glass when Eddie tells him he can’t help his nature.

Inside Roland’s story of Debaria and the skin-man is a legend from Mid-World, passed down in the form of a bedtime story called “The Wind Through the Keyhole.” It’s the type of story, young Roland says, that “‘start[s] “before your grandfather’s grandfather was born,”’” and it’s the best and most exciting of these three terrific stories. It feels similar to King’s The Eyes of the Dragon, but it’s far more humble, centered on the village of Tree – “the last town in what was then a civilized country” – and a young boy named Tim, whose father has been killed and who must go on a dangerous quest to save his mother. If this sounds similar to the plot of King’s and Peter Straub’s The Talisman, it’s supposed to; that novel expanded on classic story archetypes, while the tale of Tim is the archetype. It’s a difficult task King sets for himself, making this story feel at once familiar and careworn but also exciting and new. That he succeeds effortlessly is a testament to King’s utter familiarity with the landscape, and his ability to translate that landscape to readers.

Tim, armed with deliberately misleading prophecies (bestowed by The Covenant Man, an incarnation of Marten … who, himself, is an incarnation of Randall Flagg), must face unknown dangers lurking in The Endless Forest, a vast unexplored wilderness serving as the apotheosis of Grimm’s many fairy-tale woods. Hansel and Gretel, Little Red Riding Hood, and Snow White would recognize it at once. While there are classic fairy-tale elements here (dragons and tigers and fairies, oh my), and a fascinating appearance of Great Old Ones technology (sort of a GPS device crossed with iPhone’s Siri), here King subtly begins to assert the presence of stories from our world into the history of Roland’s world. Early in his quest, Tim is led astray by an analogue of Tinkerbell, from Peter Pan. Later, he faces creatures that seem distinctly related to Swamp Thing, the DC Comics character. This is part of the reason why The Wind Through the Keyhole is a necessary book: the shift from the Oz fascination of Wizard & Glass to the Magnificent Seven/Harry Potter/Doctor Doom/’Salem’s Lot onslaught in Wolves of the Calla needed a better bridging element. If read as King intends, in between those two books, Keyhole mentally and emotionally prepares the reader for these fictional intrusions on reality.

None of these disparate elements distract from Tim’s grim, exciting journey. Because he is young and accepts everything readily, the reader is more than willing to follow suit. Because Tim’s story is a fairy tale, the ending isn’t ever much in doubt (there has to, after all, be something of a happily ever after), but then the entirety of The Wind Through the Keyhole is like that. Because contradictions of both Roland’s past and the story of “our” travelers would derail the story, nothing about this book can upset the status quo too much. Thus, Keyhole is an exploration of one of King’s most important Dark Tower themes, that the journey is far more important than the destination.

Whether readers loved or loathed the ending of the Dark Tower, a book like The Wind Through the Keyhole offers intriguing possibilities. The idea of further books set in Mid-World – whether along the path of our travelers (or at least set in their time), in Roland’s past, or in legend – is appealing, owing to both the long history and vast expanse of King’s fantasy world. In an authorial note midway through the book, King indicates that “The Wind Through the Keyhole” is only one story from The Great Elden Book, “a fine and terrible compendium that may someday merit publication of its own, as those stories cast light on Mid-World as it once was.” While King may have come to his conclusion (if not the conclusion) of his primary story, The Wind Through the Keyhole proves out one of his long-standing adages: here, sir, there are always more tales.