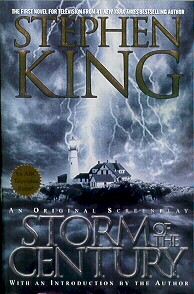

| Storm of the Century |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

|

Novels such as 'Salem's Lot, Desperation, It, The Tommyknockers, Needful Things, and The Regulators all feature stories of insular and/or isolated small towns with which an outside evil decides to use or destroy. It is a familiar Stephen King theme; though told with compelling variations, the basic structure remains the same: in order for the town to survive, the people in it must band together to save it ... or suffer the consequences.

What if, King poses in his introduction, the opposite were true? What if by banding together the townsfolk only make it worse?

Continuing a thread King first explored in Bag of Bones, Storm of the Century sets about answering those questions. Set on Little Tall Island, most recently the home of Dolores Claiborne, Storm of the Century opens with a sequence of unmitigated violence. Several of King's more recent books - Rose Madder, Insomnia, and The Regulators chief among them - have employed similar openings, preparatory chapters that act almost as a warning for the horror to follow. Here, a stranger named Andre Linoge has come to Little Tall, proceeding what meteorologists are terming the "storm of the century," a super-blizzard set to besiege the island within hours. Linoge enters the screenplay softly, humming “I'm a Little Teapot” (this repeated refrain suggests a clever appropriation of the phrase “tempest in a teapot,” an apt description of the coming storm and the island community it traps) on his way up to an old woman's home. She lets him in, and he beats her to death with his cane.

Enter town Constable Michael Anderson, who is also a husband and father. Unable to send Linoge to the mainland because of the storm, he keeps him locked in a cell at the back of the general store. Before he reaches his cell, Linoge unleashes uncomfortable, prescient knowledge: seemingly knowing what everyone's darkest secret is, and sharing his information with everyone. In this way, Linoge is like Leland Gaunt, of Needful Things, sowing discord through a community by forcing people to confront their deepest secrets. The major difference here is that Linoge doesn't bother with trickery or subterfuge, relying instead on people's innate fears of their hidden selves to play them against one another.

Much is made of Linoge's long life and supernatural powers - including the ability to make people kill and harm themselves, an echo of the version of Tak we see in The Regulators - reinforcing similarities to Leland Gaunt (as well as other like creatures in King's canon, such as Randall Flagg and Ardelia Lortz from “The Library Policeman”). Through a vision, Linoge claims to be responsible for the infamous “Lost Colony” of Roanoke Island, a group of settlers who disappeared without a trace between 1585 and 1587. “Give me what I want and I'll go away,” Linoge repeats, and in his vision, shows how he forced the settlers of Roanoke Colony to commit mass suicide by throwing themselves in the ocean. The historical details of Roanoke provide intriguing backdrops for King's story: Little Tall is meant to parallel Hatteras Island, on which the Lost Colony supposedly settled, and an attempt by the British to return to Roanoke in 1590 was thwarted by hurricane - an earlier “storm of the century.”

King has long worked with symbolic names as character clues: here, the name “Linoge” is an anagram of “Legion,” indicating the Biblical entity comprised of many demons. This understanding is crucial to an understanding of Storm of the Century; while Linoge himself is evil, he works in uncovering and using the evil in regular people. The Biblical story of Legion is also important: when Jesus cast the collective Legion out of a man, the demons then dwell in a herd of pigs, who then drown themselves in the Sea of Galilee. This imagery is echoed in Linoge's vision of Roanoke's mass suicide; by marching the settlers two by two into the sea, it is also a reversal and perversion of the story of Noah's ark. King's use of Biblical imagery and allusion here continues a trend begun earlier in The Green Mile and Desperation (and would continue through The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon). But while those books offer at least a semblance of hope, Storm of the Century offers only the darker side of religion, though misplaced ideas of trust and faith, and the consequences of false belief. Its ending, one of King's most downbeat, seems more at home with the Bachman novels than with King's often cautiously optimistic endings.

Storm of the Century is only King's second published full-length screenplay, following 1983's Silver Bullet. While Silver Bullet is a good, quick read, Storm of the Century is far more developed and compelling. Frustratingly, King's other produced screenplays - including those for Creepshow, Maximum Overdrive, and the later original miniseries Rose Red - remain unpublished, robbing readers of the chance to watch King's progress as a screenplay writer. As such, Storm seems a sudden leap in confidence and comfort with the medium. Perhaps given the nature of Silver Bullet as a feature film, the screenplay seems thin and somewhat rushed. Storm, being a miniseries, allows King more space to further develop characters and situations in the screenplay. Perhaps the fact that it is an original work, not based on King's existing material, also forces readers to look at it more objectively, allowing readers to evaluate it by itself, rather than as a comparison to more familiar prose.

An engaging, accessible work, Storm of the Century is unique in King's canon, but in furthering King's late-90s themes and fascinations, it also fits in with King's more traditional prose. The miniseries based on the screenplay, directed by Craig R. Baxley and starring Timothy Daly, is among King's best filmed works, easily the best of his television ventures, further elevating Storm of the Century's status as a major Stephen King work.