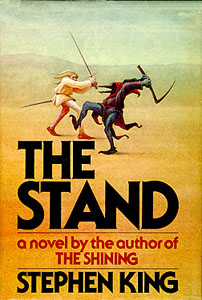

| The Stand |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

|

For second- and third-generation readers (those who were born after Carrie was published, and especially those who began reading King in his third decade of publishing), reading the initial publication of The Stand is almost a novelty, or an experiment. Infamously, when The Stand was first published, Doubleday forced King to cut down the manuscript so they could shave a dollar off the cover price. Faced with the option to cull the pages himself or have the editorial department do it, King reluctantly trimmed a quarter of the novel's length. The public, having no knowledge of these cuts, responded enthusiastically, putting The Stand on the bestseller lists both in hardcover and paperback.

As Stephen King's popularity grew, so too did the popularity of The Stand. In 1990, still irritated by the imposed cuts, and now with far more influence on the market than he had in the late 70s, King published a new version of The Stand. He reinstated the missing pages and updated the cultural references to make it relevant to a new generation. This unexpurgated version effectively put the earlier, "cut" version out of print ... which brings up an important question: with no pun intended, where does the original version stand? It's no longer in print, but does that mean it's extinct? And the larger question: how much right does a creator have to tamper with his own published work, even if that published work was not his original vision?

Those newer readers would almost surely have picked up the "complete and uncut" version first. Fans then curious about the evolution of the novel may go back and read the original. The process then becomes a reversal of readers who had been following King's career from the beginning: subtraction now, instead of addition – excisions after the fact. In a sense, new readers have experienced the book in the order in which it was written – not published – first with King's initial vision intact, and then with the mandated cuts. It's a fascinating process to bear witness to.

In the foreword to the uncut edition, King states that readers will not "see characters behaving in new and unexpected ways," but he allows as to how we may understand them more fully. Again, a reversal: those more familiar with the unabridged version may feel a disconnected from what was going on. Beyond the characters, the narrative itself seems lacking. The initial threat of the Captain Trips virus seems almost arbitrary, simply a device to move the plot along. Eventually, the characters' reactions to it bring it to a human level, but until Larry is confronted with his mother and Frannie has to bury her father, the virus itself seemed like a looming threat peripheral to our main characters. In the uncut version, the opening with Campion and his family escaping, humanizes the virus at once, making the immense devastation later that much more relatable.

Many of the characterizations are intact. Stu Redman remains the stoic, reluctant hero, Larry Underwood is still the childish rock star who is forced to mature in the wake of Captain Trips, Nick Andros still quietly chooses the righteous path over the easy path. Some characters, though, suffer. Frannie remains somewhat of a mystery, little more than a reactor to men's motivations. The conflict with her mother in the unexpurgated edition seems vital in drawing her character as fiercely independent. Vital, too, seems Trashcan Man's trek across the desert, and his confrontation with the brutal rapist known as The Kid. In this earlier edition, Trashy disappears for time, then shows up out of nowhere with a nuclear missile. It works to a degree, but it works better in the later edition. The ending of the 1978 version borders on abrupt, cutting quickly from the explosion in Las Vegas to Stu and Tom's return to Boulder. Without the scenes of their journey back, we are robbed of some interesting character moments toward the end of the book, none of which are strictly necessary, but which add a flavor and a sense of optimism after all the death in Vegas.

In the end, it seems, comparisons are inevitable. The question remains, though: is the 1978 version still an integral cog in the machinery of King's published work? Many King fans swear by it, stating that "less is more" and thinking the newer version indulgent. Other fans have gone the route that King seems to have prescribed: replacing the 1978 version with the 1990 version.

Perhaps both editions are necessary. Certainly the 1990 version is a richer and fuller story, with more room to let its characters breathe. But the 1978 version came to be considered a classic, and it's a vital step in reading King's early work. The sociopolitical backdrop of The Dead Zone seems like a giant leap from the insular tales of Carrie, 'Salem's Lot, and The Shining; The Stand makes that leap more comprehensible. Though perhaps not as rich as the unexpurgated volume, this version of The Stand finds a young writer working to refine – and exceed – concepts explored in his first novels; in short, it showed the world what Stephen King was capable of.