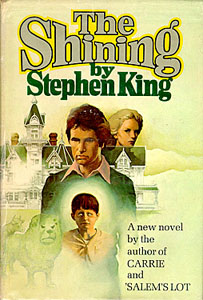

| The Shining |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

|

Stephen King's most frightening novel is the result of a night King and his wife spent at The Stanley Hotel in Colorado. The hotel was set to close for the season the following day, and Stephen and Tabitha King were the only guests of the hotel. The seclusion of the setting helped refine a story called Darkshine King had been mulling over, about a child with psychic powers trapped at an amusement park. A dream King had that night about his three-year-old son being chased by a living, malevolent fire hose further helped the story coalesce. "I got up," King stated later, "sat in the chair looking out at the Rockies ... [and] had the bones of the book firmly set in my mind."

The Shining is, like many early King novels, a study in isolation. Carrie White is set apart from her classmates and demonized by her mother, forced to lead a largely solitary existence. The slow transformation of 'Salem's Lot would not have been possible without the willing seclusion of its townspeople. In The Shining, King eschews the populous casts of his previous novels to focus solely on the three members of the Torrance family: Jack, Wendy, and Danny. Simply by reduction, King introduces a somewhat claustrophobic element at the outset (a device King later explored in Misery, featuring two characters, and Gerald's Game, featuring one). By placing them in the hulking Overlook Hotel in the shadows of The Rockies - and eventually cutting them off from all civilization - King escalates the twin themes of isolation and claustrophobia, raising the level of tension to nearly unbearable degrees.

As early as the opening line - "Jack Torrance thought, officious little prick." - Torrance comes across as adversarial. He is a damaged man whose deep flaws have damaged others. A recovering alcoholic, Jack is given to fits of temper and rage; addiction seems to be less a cause than a symptom of his deeper character issues. Once, when his son Danny spilled a can of beer over his important papers, Jack yanked him away and accidentally broke his arm (the imagery of alcohol damaging Jack's work is not accidental). Later, while sober, Jack beat up a student of his for slashing his tires; alcohol is not necessarily a trigger for these outbreaks, merely an accelerant. When Jack agrees to take the position of winter caretaker at the Overlook, it is quite literally his last chance to change and prove himself responsible.

Danny, Jack and Wendy's son, has a personality diametrically opposed to Jack's. At six, Danny's primary concerns are keeping his parents (especially his father) happy and together. One of King's "wild talent" children, Danny Torrance is revealed early on to possess strong telepathic abilities. (It is worthy to note that, while King simply asserts Carrie White's telekinesis two books prior, he reveals Danny's talents more organically here. King's growing maturity and assuredness as a writer is fully on display in these early novels.) As a by-product of his ability, Danny's child's-eye view of a normative family is frequently disrupted. As some children may sense unease between their parents, Danny is able to glean specific problems, picking up words like self-image, divorce, even suicide. Due to his age and inexperience, Danny is unable to fully grasp the implications of these terms. (King would later explore this concept to a lesser extent in Pet Sematary, in Ellie Creed's struggle with terms and symbolism in her prophetic dreams.) Never is this more explicit than in the recurring term redrum, which seems to point toward Jack's alcoholic past, but instead mask a much darker meaning.

The Overlook itself is an extrapolation of The Marsten House of 'Salem's Lot, functioning in the Gothic tradition as a brooding Bad Place. Intellectually, Jack is aware of the hotel's notorious past; the hotel boasts a seemingly endless series of murders and suicides. Though Danny senses the more immediate danger of the Overlook, he chooses to ignore the warnings, believing his father's need for the job more important. A young child forced into making adult decisions is a common motif in King's writing; Danny Torrance is the predecessor of Charlie McGee of Firestarter, Jake Chambers of the Dark Tower series, Marty Coslaw of Cycle of the Werewolf, Jack Sawyer of The Talisman, David Carver of Desperation, Trisha McFarland of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, and the Loser's Club of It.

While his parents have a vague understanding of his abilities, it is only in the Overlook's departing cook, Dick Hallorann, that Danny finds a true ally. Surrogate parents capable of believing in King's troubled children often stand in for distant or damaging parents, especially in his early work. (It's interesting to note that attempts to seek refuge in peers - such as in Carrie or Christine - often end tragically.) Hallorann gives name to Danny's telepathic ability, referring to it as the shining, and confides that he has similar - if weaker - talents. Hallorann serves the Gothic tradition as the person who knows secrets, confiding that those with the shining can often see things in the Overlook that others can't. The notion of a place echoing negative emotions and violent events associated with it, first explored in Ben Mears's ambiguous psychic vision of Hubie Marsten in 'Salem's Lot, would later recur overtly in Christine and more subtly in It (a novel in which Hallorann briefly appears). That Hallorann turns out to be wrong - underestimating both the power of the Overlook and Danny's abilities - twists his assurance into an omen.

The Shining succeeds on multiple levels. On the surface, King's use of Gothic tropes in a modern setting works extremely well: the Overlook is the old castle, Danny's visions prefigure tangible supernatural activity, and Wendy Torrance is the woman in distress ... though not as helpless or passively suffering as those in traditional literature, as is Sheridan Le Fanu's Laura or Poe's Madeline Usher. Much of the terror springs from the modern world (especially King's famous use of brand names) being subverted by the supernatural. Though atmosphere, tone, and setting all suggest horror tradition bordering on stereotype, King's modern language and investment in the inner lives of his characters force the reader to believe in them and their situation.

Symbolically, the Overlook's preoccupation with its violent past mirrors Jack's destructive personality. Mistreated as a child by his father, Jack is unable to break the cycle of anger and abuse. Jack's discovery of the hotel's scrapbook allows him to wallow in the hotel's past without being aware of its hold on the present, or its affect on his son; the scrapbook becomes a clouding addiction as destructive as his alcoholism. Danny's confrontation with the dead woman in Room 217 echoes the moment that Jack accidentally broke his arm. Assured implicitly or explicitly by father figures that he will not be hurt, Danny is injured. It is telling that one of Jack's first responses to Danny's injury is to blame someone else, misreading Danny's cries of "It was her!" as an accusation of Wendy. The concept of responsibility is central to Jack's character; though he takes credit for his successes, he continually blames his failures on others. Perhaps on some level, Jack is aware - and jealous - that the hotel is not really interested in him, and that it is Danny and his extraordinary ability that it craves. The Overlook exploits these flaws to corrupt Jack entirely, only able to fully flex its will on him after he begins to blame his family for his failings.

Early paperback printings of The Shining boast that it is "a masterpiece of modern horror." It is hard to argue with that assessment. Only a handful of King's novels have the capacity to terrify as readily as The Shining, with Pet Sematary and 'Salem's Lot coming closest. It is a consistently readable novel, paced quickly but paradoxically allowing its horrors to emerge deliberately. King elevates mundane objects - the hedge animals, the fire hose, the cylinder in the playground - into sources of horror, without sacrificing believability (a device he had honed with stories such as "The Mangler" and "Trucks," and that would recur later in "The Monkey" and The Tommyknockers). By the end of the book, Jack, having rendered Wendy helpless, chases Danny through the hotel with a roque mallet, bellowing. Both on the surface and in its implications, it is among King's most horrifying sequences. Second- and third-generation readers, approaching the novel in the wake of a movie adaptation that misunderstood the nuances of the book and a television adaptation that, while faithful to the word, failed to capture its spirit, may be surprised by its sheer narrative force. In addition to being one of King's scariest works, it is also one of his finest, still intellectually and viscerally effective after three decades.