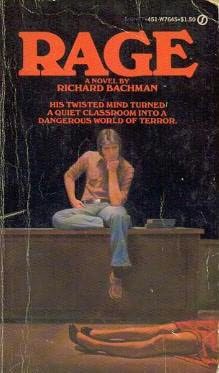

| Rage |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

|

After being expelled from school for assaulting his shop teacher, Charlie Decker, the unstable and perhaps unreliable narrator of Rage, shoots his math teacher and takes his classroom hostage. What once might have seemed like a disturbing if understandable idle fantasy has, in the years since Rage was first published, become an increasingly tragic reality. In his foreword to the re-released omnibus edition of The Bachman Books, King hints at the unease he has with Rage, and with the young man – King was still in high school when Rage was begun – who wrote it. Three years later, in the wake of a school shooting whose perpetrator had a copy of Rage in his locker, King withdrew the novel from publication, incidentally rendering Rage the only book-length King novel out of print. Explaining his intentions during his keynote address at the Vermont Library Congress annual meeting, King stated that while a novel like Rage may not be the cause of violent behaviors, it “may act as an accelerant on a troubled mind.”

Charlie Decker, King’s antihero of Rage, is certainly troubled. Before the end of Chapter One, he freely admits that he has lost his mind. Pop psychology would diagnose him at first glance with a persecution complex and delusions of grandeur, both evident in his confrontation with his principal. “You’re not qualified to deal with me,” he states, then goes about proving himself intellectually and morally superior to every adult figure in the book. Understanding the precepts of pop-psych is important: Rage is a young Stephen King’s revenge fantasy as much as it is Charlie Decker’s, and the limited understanding of psychology and therapy comes through in both the language and action of the novel.

The murder of Mrs. Underwood, Charlie’s algebra teacher, seems almost beside the point. Charlie taking his algebra classroom hostage – he refers to this as “getting it on,” the original title of the novel – is the real meat of Rage. From almost the moment he shoots Mrs. Underwood and takes control of the class, they are (mostly) willing participants in his megalomania. With the class under his thrall, Charlie relates stories about his father and how a traumatic camping trip provided the basis for his eventual instability. Though overly simplistic, the damaging relationship between Charlie and his father foreshadows King’s later, more complex issues between parents and children. Carl Decker is the schematic from which the more nuanced studies of Margaret White (Carrie), Jack Torrance (The Shining) , Al Marsh (It), Elmer Chambers (The Waste Lands), and Tom Mahout (Gerald’s Game) are constructed. Interestingly, a book written not long after Rage was completed – the later Bachman novel Blaze – features in Clayton Blaisdell, Sr. a father figure even less realized, abusive for no other reason than that he can be.

Charlie invites his other classmates to divulge their worst memories and darkest secrets, and for the most part, they are happy to comply. King seems to suggest that this instantaneous Stockholm syndrome springs from his classmates’ strong identification with Charlie’s anger. It is almost as if they had been waiting for something to shake them out of their miserable existences, and that Charlie’s sudden and violent intrusion is actually welcome. While none seem to approach Charlie’s purported psychosis, most of the class seems to agree with his assessment of the adult world: it is not qualified to deal with them.

The sole holdout is a boy named Ted Jones. Very early in the story, Charlie remarks that only he and Jones had passed a particularly difficult exam. There is some indication that Charlie sees Ted as his intellectual equal, but finds his values skewed. While many of Rage’s characters attain some level of depth, Ted remains one-dimensional, working only as a threatening symbol of adulthood. Similar themes later emerge in Christine and, to some degree, It: growing up is a threat and a danger to overcome. The class’s violent uprising against Ted by the end of the book renders him incurably catatonic, a change so swift and drastic that it stretches credulity, furthering the notion that Ted isn’t really a person, merely a representation. Despite these shortcomings, the sequence is still powerful, recalling scenes from William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, an important King influence. Much later, King would return to the symbolism and allegory of Golding’s work in Hearts In Atlantis and Blockade Billy.

While the Bachman have connections to books written under King’s name (mostly thematic, but occasionally places and characters), analyzing them as a separate group is interesting. As King developed Bachman’s meta-personality, a unique style developed throughout the books published under Bachman’s name. Rage is a dark novel with a bleak ending, its main character fundamentally damaged by the events in the book – a blueprint for nearly every novel written under the Bachman name with the (possible) exception of The Regulators. Its almost casual violence carries over to the other Bachman novels as well, as does the “countdown” structure (the classroom’s wall clock here prefigures the murdered Long Walkers, Billy Halleck’s decreasing weight, the time and date stamp heading chapters in The Regulators, and of course The Running Man’s literal countdown).

Tonally, Rage is of a piece with the earlier-written Bachman novels, including Blaze. Though still rough and developing, King’s sense of mood and pacing is already on display here: these early books move fast, though almost quietly, as if King’s Bachman voice comes out as a whisper. (Interestingly, both Cujo and Dolores Claiborne – written under King’s name – are more reminiscent of the flavor of these early novels than either Thinner or The Regulators.)

In his foreword to Blaze, King briefly touches on Rage being taken out of print, calling it “a good thing, too.” While that may be true, Rage represents a nascent storyteller finding his voice, employing themes and motifs he would later refine. It remains very readable, engaging and fast-paced enough to read in a single sitting. As the earliest published example of King working with the novel form, Rage, despite its flaws, still remains vastly important to a full analysis of Stephen King.