Limited Edition Information

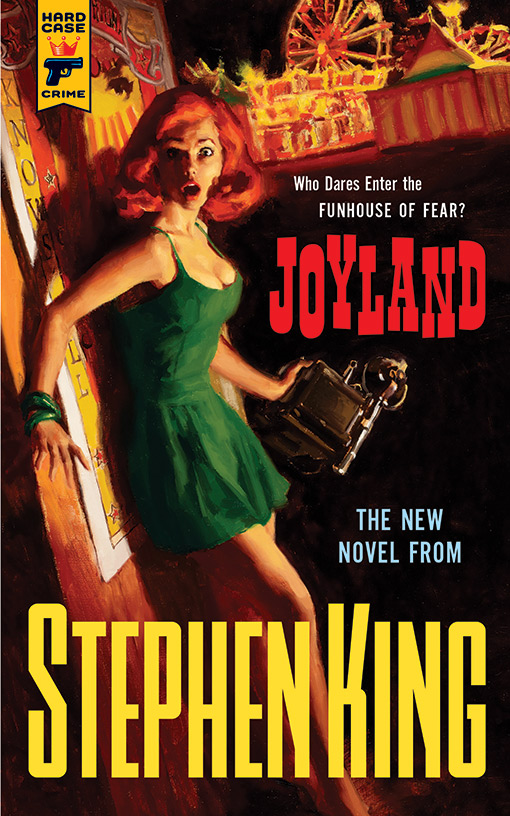

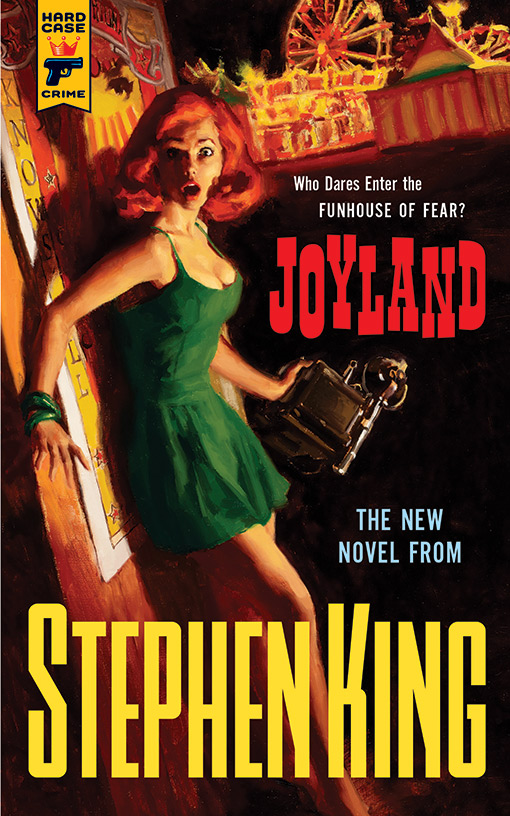

| Joyland |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

Limited Edition Information

|

Thereís a certain flavor to Stephen Kingís 1970s novels that goes deeper than theme and tone and even feel, especially in the smaller, more personal stories like The Shining and íSalemís Lot and The Dead Zone. The books are certainly ďof their time,Ē but itís more than that: itís a distinct spirit thatís difficult to pin down and even harder to describe. These books Ė as well as the Bachman novel Blaze, a relic from those early days Ė come from such a distinct time, place, and mindset in Kingís career that the stories canít help but reflect who and where their author was when they were written. Cheese aficionados and wine connoisseurs call this elusive essence terroir. At this late date, decades after those classic novels were published, it would be almost impossible to capture that exact flavor again, in a new novel written by a man much older and with far more experience.

Almost impossible. Stephen King did it, nearly forty years later, with Joyland.

Itís a simple story: college junior Devin Jones takes a summer job at an amusement park called Joyland Ė itís no Disney World, but itís grander than a county fair. Thereís a mystery at the heart of the park, an unsolved murder committed inside the Horror House. Thereís also a ghost: the dead womanís spirit, some claim, still haunts the Horror House. She was holding out her hands, one witness says, like she was asking for help.

Both the mystery and the ghost come into Joyland fairly early, and while neither quite disappears, for a long time they seem beside the point. The first half of the novel is more concerned with the simple act of watching Devin Jonesí summer unfold ÷ and a glorious summer it is. Given the setting (and the important appearance of a tattoo), itís tempting to think of Ray Bradburyís Something Wicked This Way Comes, but itís not that sort of carnival story. Dev Jones is a good-hearted young man who revels in simple pleasures; that sort of story can become dull in the wrong hands, but King takes Devís easygoing summer at Joyland and weaves it into something exciting and magical; in terms of Bradbury comparisons, itís more Dandelion Wine than The Halloween Tree. It also recalls Hearts in Atlantis, in both its intense boy-girl-boy friendship and its college tale of first loves and losses, and the complicated emotions and decisions spin that from those things. Thereís also a touch of 11/22/63: King allows us to engage in the small excitements of Devís life as he previously let us watch the easy way Jake Epping takes to living in the past.

Along the way, we get a lesson in The Talk, lingo that the Joyland folk toss around; itís fun and immersive in an approachable way, somewhat opposite from the relationship language in Liseyís Story, which had the tendency to be distracting. Then thereís Howie the Happy Hound and Devís reaction to being him. King has a way of making mundane moments feel transcendent, like when Rosie McClendon stands in her new apartment for the first time in Rose Madder, or when Roland Deschain dances in Wolves of the Calla. When Dev Jones puts on the Joyland mascot costume for the first time, itís as exciting and absorbing a scene as any in Kingís more kinetically charged horror novels.

Of course, the murder and the ghost never completely leave Devís (or Kingís) mind, and as the Joyland summer turns to fall, things grow more serious. While thereís some clairvoyant activity throughout the early part of the novel Ė dire warnings from carnival mediums Ė midway through the book, we are introduced to Annie Ross and her son, Michael, a sick kid with a psychic gift. In two of the bookís more exciting sequences, we learn that Annie isnít without talents of her own. Devís relationship with these two is as engaging as his friendships with summertime housemates Tom Kennedy and Erin Cook, but the change in season heightens things. If his Joyland summer is, as Dev thinks, the last summer of his childhood, this is the first fall where he has to be a grownup. The days get shorter and colder, and the mystery of the slaughtered girl in the Horror House slowly emerges from the background. Unlike in Kingís previous Hard Case Crime outing, The Colorado Kid Ė which functioned as something of a metatextual examination of the nature of mystery Ė here we get a very satisfying resolution to this particular puzzle. Misdirection and red herrings abound, delightfully, and the weather-ravaged denouement could play out as the conclusion to a Donald Westlake or Lawrence Block novel. As usual, King slips in and out of genre effortlessly, but itís gratifying that at the core of Joyland exists a story worthy of being called a Hard Case Crime.

In his early career, Stephen King tried his hand at a novel called Darkshine, about a psychic boy trapped in an amusement park. He took those basic components and transformed them into The Shining, but it seems as if some of those ideas Ė and the impetuses behind them Ė lingered on. In the context of Kingís larger career Ė coming right after the Dark Tower midquel, The Wind Through the Keyhole, and the sequel to The Shining, Doctor Sleep, both books in part trading on Kingís long legacy as a writer Ė Joyland should feel small. Instead, it feels fresh, and incongruously bold, like a lost book from Kingís first days as a struggling writer with something to prove.