news won't wait

| The Colorado Kid |

|

|

Publication Information

2005

Hard Case Crime

179 pages

Paperback Original

Limited Edition Information

Published by PS Publishing

All limited editions are hardcover. Art is divided across all limited formats by three artists: JK Potter, Glenn Chadbourne, and Edward Miller.

99 copies; traycased, gilt-edged, leather-bound hardcover signed by King and all three artists

- 33 illustrated by Chadbourne

450 copies; slipcased hardcover signed by King and artist

- 150 illustrated and signed by Potter

- 150 illustrated and signed by Chadbourne

- 150 illustrated and signed by Miller

1,000 copies; hardcover signed by artist only

- 333 illustrated and signed by Potter

- 333 illustrated and signed by Chadbourne

- 333 illustrated and signed by Miller

10,000 unsigned copies

- 3,333 illustrated by Potter

- 3,333 illustrated by Chadbourne

- 3,333 illustrated by Miller

|

A Novel Critique

Wanting might be better than knowing. With this sentence, found in the Afterword section of The Colorado Kid, Stephen King underlines everything that this small book has to say about the nature of mystery. It also goes a long way toward explaining one of King's more fascinating recent motifs.

This novel (at 179 pages, it's even shorter than Carrie), concerns the mystery of The Colorado Kid, a man discovered early one morning propped up against a garbage bin on the beach of Moose-Lookit Island, off the coast of Maine. More accurately, that mystery is at the center of the book ... but the book doesn't really concern The Colorado Kid. As the characters state over and over, the story of The Colorado Kid isn't really a story at all, in part because stories need a beginning, a middle, and an end. At the heart of this tale is an incident with no resolution, an unsolved mystery that remains unsolved, even after the turn of the last page.

King states in his Afterword that there are some readers who will be unhappy by this lack of resolution. He may be reacting to concerns about similar ambiguity in recent books like From a Buick 8 and especially The Dark Tower, whose finale depended upon readers accepting that the journey was more important than the destination. However, while these books - as well as the upcoming Cell, and recent short stories like "Everything's Eventual" and "L.T.'s Theory of Pets" - offered complete stories with open endings, The Colorado Kid introduces a mystery and deliberately doesn't solve it. In this way, The Colorado Kid hews closer to the Everything's Eventual short story "All That You Love Will Be Carried Away". As these stories aren't concerned with concrete answers, other factors like character, style, place, and the appeal of their central questions are all that more important.

These elements shine in The Colorado Kid: surrounding the mystery at its core is another, gently compelling story involving two old newspapermen - David Bowie and Lewis Teague, fun pop-culture names - and one young newspaperwoman, named Stephanie McCann. Beginning with a clever opening that both introduces us to the characters and teases us with a duo of minor mysteries (these ones with explanations) to get us in the right mindset, the novel takes on a friendly, folksy quality, despite the fact of the dead body in the middle of things. Charm aside, Teague and Bowie have ulterior motives. Through introducing Stephanie to the bafflement that is The Colorado Kid, they're also testing her, seeing if she's fit to be "one of them," even if she is from off-island. (King's ongoing curiosity with Maine island communities and the people who populate them - as in "The Reach," "Home Delivery," Dolores Claiborne, and Storm of the Century - continues to be one of his most compelling idiosyncrasies.) "School is in," Bowie and Teague tell her, and it's to Stephanie's credit that she's not only willing to learn; she's eager, somewhat to her chagrin.

What unfolds, then, is the tale of a dead body, where it was found, and an investigation into how it got there, told in voices King knows and uses well. It's the voice of the kindly old gent telling you a tale that might be scary and it might be hard to know ... but it isn't hard to hear. It's the same voice readers recognize from the beginning of Needful Things: "You've been here before, sure you have." It's Paul Edgecomb's voice in The Green Mile, minus the slight Southern affectations, and anticipates the narrator of the similarly-structured Blockade Billy. It's a down-home Yankee sort of storytelling, and as the plot quietly cycles into motion, it almost (but not quite) feels arbitrary. King obviously loves these characters and wants readers to love them, too; while the mystery is compelling, listening to these three people talk is the primary pleasure of The Colorado Kid.

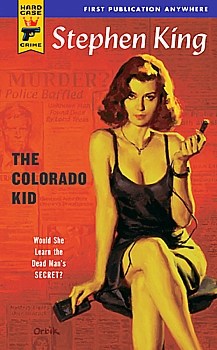

Since 2004, the imprint Hard Case Crime has published an ongoing series of noir and crime novels, both reprints of classic pulp fiction and new work by current writers, written in the same spirit and style. The publisher initially contacted King to write a blurb for the series and, in true Stephen King style, ended up with an entire novel. The books feature terrifically pulpy new cover artwork; Glen Orbik, whose seductive art for The Colorado Kid is hilariously unrelated to the story inside, would later go on to do the cover for King's short book, Blockade Billy. Interestingly, as The Colorado Kid subverts the intentions of the Hard Case Crime line - no sex, no violence, and no actual crime - the later Blockade Billy seems to fit the line perfectly. It would be published by limited edition publisher Cemetery Dance, and reprinted by Scribner in 2010.

Reaction to The Colorado Kid was mixed, as King assumed it would be. Some critics and fans hated the lack of resolution (the Washington Post going so far as to call King "perverse," and the novel "agonizing") and others enjoyed its clever commentary on itself (The New York Times liked it, calling it "postmodern.") Still, the uncomplicated joy of getting to know these new people was welcome in the wake of King's massive three-volume Dark Tower finale. Despite some similarity in intent between The Dark Tower and The Colorado Kid, here the quiet meditation on the nature of mystery without solutions is not beholden to a career-long epic. Perhaps the ambiguous nature of The Colorado Kid works better in part because King explains himself a bit in his chatty Afterword. He not only backs up why he chose to let the mystery of The Colorado Kid go unsolved, but how he came up with the concept in the first place. In other words, even though we never know the answer to the mystery, King clears up the mystery behind the mystery.

One final note: there are real-world inconsistencies in the novel, chief among them the existence of a Starbucks coffee shop in Denver, Colorado in 1980. In reality, Denver didn't get a Starbucks until 1992 - a continuity error King explained later on his message board as a clue, indicating that there may be a connection between The Colorado Kid and his Dark Tower series. It makes sense: the latter books of The Dark Tower explore parallel universes and the ability to travel between them. But an understanding of The Dark Tower isn't necessary to enjoy this small, fascinating novel. Despite its open ending and hints of larger implications, The Colorado Kid seems complete, and stands on its own.