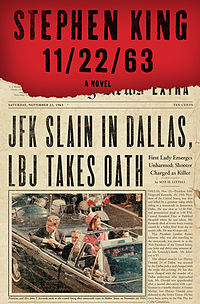

| 11/22/63 |

|---|

|

| Publication Information

|

Near the start of 11/22/63, ailing and aging Al Templeton – proprietor of Al’s Diner in Lisbon Falls, Maine – informs his teacher friend, Jake Epping, that his diner’s pantry inexplicably leads to the year 1958. There are rules to this particular form of time travel, too: the person who goes back to the past always arrives at the same time and place, and each trip back to 1958 resets every change he’d made on a previous trip, wiping the slate clean. When he returns to the present, it’s always just two minutes later than when he’d gone, no matter how long he’d been away. And there’s the almost Gothic presence of the Yellow Card Man, who sits drunkenly at the exit into the past, and who may know more than he lets on. It’s overwhelming information, and before Jake can even begin to process what he’s learned and seen, Al forces a twofold mission on him: to determine whether Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, and if so, stop him from assassinating President Kennedy.

It would be easy to dismiss time travel as a MacGuffin, Alfred Hitchcock’s word for the contrivances that get the story going but ultimately aren’t all that important. Certainly there’s no science to the method that takes Jake Epping back to 1958, no contraption or explained temporal field or reasoned-out wormhole. It just sort of happens. Al Templeton, prosaically, uses it to buy dirt-cheap 1958 meat for his diner and turn it into 2011 profits. There’s some lip service paid to inherent time-travel paradoxes – like what would happen if a man killed his own grandfather – but King is only marginally interested in the science elements of science fiction. As always, he’s far more concerned with people, and why they do what they do, and what consequences their actions have. King does raise some interesting SF questions, like how Al can keep buying the same meat over and over again and serve it anew in the future, but ultimately he leaves these questions unanswered.

Part of what compels Jake to go on his mission is an essay by one of his adult students, Harry Dunning, describing the night in 1958 when his father murdered his family and crippled him, Harry. Knowing he can stop the slaughter, Jake travels back ... but, as he repeats throughout the book, “the past is obdurate.” It does not want to be changed. 11/22/63 isn’t a horror novel, but King doesn’t flinch back from Jake’s dark, messy business with the Dunning family. It’s one of the few truly scary scenes in the book, and both the mistakes made during it and the consequences following it should warn Jake from trying to change the past ... but Jake is also obdurate, and once again travels back.

There’s a long section of 11/22/63 called “Living in the Past,” and it’s the book’s most compelling. It’s also a risk for King; while the ostensible reason for Jake traveling back – researching and stopping Oswald, if necessary – remains a concern, the book deftly shunts it to secondary status. Under an assumed name, Epping moves to a small town in Texas called Jodie, and in short order, becomes a substitute teacher, directs the school play, mentors students, and saves and changes lives. Most importantly, Jake falls in love. Since 1987’s The Tommyknockers, King has been exploring adult love with more nuance than in most of his earlier books (the relationship between Bobbi Anderson and Jim Gardner is far more interesting than the book’s supernatural aspects). Jake’s affair with the beautifully Amazonian Sadie Dunhill is sweet, tragic, complicated ... and ultimately one of Stephen King’s most believable love stories.

It’s to King’s enormous credit that Jake and Sadie’s relationship – and their relatively idyllic life in Jodie – is so involving and fascinating that when King returns to Oswald’s story it almost feels like a distraction. For long stretches, Jake’s mission, and the science fiction elements of his story, simply fade away. 11/22/63 allows readers to simply live inside Jake’s life and in the world of the book. While most of King’s novels are character-driven, very few feel as lived-in or expansive as this one. The Dead Zone, which took its time to define Johnny Smith as a moral, flawed, likable protagonist, is one early example; It, with its multiple timelines and ability to follow characters at two crucial moments of their lives, is another.

11/22/63’s connections to both It and The Dead Zone go deeper than simply tone and narrative speed. Before Jake travels to Texas, he has an extended stay in Derry, Maine. It’s 1958, a few short weeks after the town’s child murders came to an end, but Jake can sense Derry’s continued, underlying evil. Most interesting for readers – aside from running into some favorite (and least favorite) characters from It – is witnessing Derry from an adult perspective in 1958. While It never glossed over the dangers of its child characters, readers experience their adventures through the mostly naïve eyes of children and, later, through the sheen of nostalgia. An adult from 2011 (and, maybe more importantly, an outsider), Jake Epping quite adeptly senses the past Derry as a Bad Place, as tinctured with bad feelings and intent as The Overlook in The Shining, the Marsten House in ’Salem’s Lot, or the eponymous Black House. In this way, 11/22/63 becomes a more vital continuation of It than either Insomnia (set in Derry and featuring an older Mike Hanlon) or Dreamcatcher (featuring the ominous graffito PENNYWISE LIVES.) Later, Jake will counterpoint Derry, Maine with Dallas, Texas – specifically the Kitchener Ironworks (the site of an atrocity that killed dozens, and served as the battleground between young Mike Hanlon and one of It’s many murderous forms) and the Texas School Book Depository, from which Oswald is destined to shoot Kennedy. While King never states that the Depository has any supernatural properties, it joins the ranks of King’s Bad Places.

The connections to The Dead Zone are subtler, and more pervasive. Neither novel is particularly political, but both involve political assassinations. Jake’s long stay in Derry to stop the Dunning murders neatly parallels Johnny Smith’s investigation of the Castle Rock Strangler, both as tests of knowledge and ability and as a way to determine our heroes’ dedication to stopping killers, even at personal cost. (Sharp readers will notice the metatext commonalities, as well: a character from Stephen King’s Maine visiting one of King’s famous fictional towns – Castle Rock, Derry – in order to stop a murderer before moving elsewhere.) Both Jake Epping and Johnny Smith have knowledge of the future, and both are working to change it for the better. The main difference between Jake and Johnny is that Jake is trying to alter a past that has already happened. In The Dead Zone, Johnny Smith’s greatest obstacle is himself: his confidence in his abilities, his desire to live a normal life, and his love for Sarah all complicate the changes he knows he needs to make. Jake Epping has to contend with a past that resists change, sometimes bloodily, and makes the high stakes instantly clear.

There are also hints of Bag of Bones’s Mike Noonan and Duma Key’s Edgar Freemantle in Jake Epping, not the least of which is the fact that all three books are, unusually for King, told in the first person. Early on, Jake confesses that he has trouble crying; this feels like an echo of Noonan’s inability to ask for help, and his continued insistence that he’s fine when he’s not. Freemantle’s early experimentation with his art – curing his friend Wireman, specifically – anticipates Jake Epping’s trip to Derry as much as Johnny Smith’s trip to Castle Rock does. There’s also the fact that Freemantle travels to Florida for an ostensibly better life, just as Epping travels to Texas when he travels to the past (Mike Noonan’s vacation in Key Largo has a similar, albeit more minimal effect). Working outside his Maine milieu for these recent long books seems to have energized King, and there’s a crackling excitement in exploring new surroundings that was missing from Lisey’s Story and Under the Dome.

Interestingly, Jake never quite questions the past’s roadblocks. He simply accepts them, just as he accepts the fact that “the past harmonizes,” presenting recurring echoes of people, places, and things the longer he lives in the past. Names like Derry and Dallas, or Dunning and Dunhill, even Sadie and Jodie. For those who remember that the year 1958 held a certain resonance in King’s fiction before It, there’s even a red and white Plymouth Fury – maybe more than one – rolling through the book. It’s not Christine, but it’s bad news, just the same. Jake knows he’s changing the future, his present, but only very late in the novel does he begin to understand exactly why the past is so resistant to change, why it remains so obdurate. In a dark reversal of Johnny Smith’s story, there comes a time in 11/22/63 when Jake is forced to question whether not using his unique powers and knowledge would be better for the world ... even if, like Johnny Smith, this decision comes at great personal cost.

11/22/63 is a powerful, entrancing novel, taking the threads of a careworn science fiction concept and weaving a fantastic romance from them. It references King’s past work – It, The Dead Zone, Christine, and, oddly enough, The Running Man – but never feels dependent on them, as The Tommyknockers and Insomnia did. Coming after the uneven and overlong Under the Dome, the stark domestic terrors of Full Dark, No Stars, and more recent impactful short horror stories like “The Little Green God of Agony” and “The Dune,” 11/22/63 is a bit of a surprise: an almost gentle, quiet novel that is nevertheless suspenseful and exciting throughout. Another seeming contradiction: despite being nearly 850 pages – much of that spent following Jake Epping’s life in Jodie, Texas – the book feels taut, filling out its length with no unnecessary pages. What seems most remarkable is that, nearly four decades into his career as a novelist, Stephen King has delivered one of his best books yet.