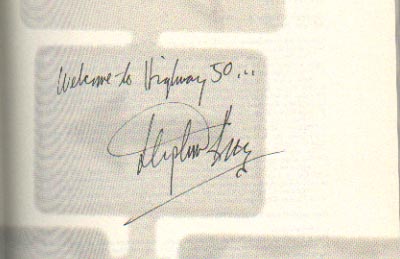

Limited Edition Information

| Desperation |

|---|

|

| Publication Information

Limited Edition Information

|

Religious themes have always been important to Stephen King's work. In Carrie, Margaret White is presented as a religious fanatic, interpreting the words of the Bible literally and, eventually, devastatingly. Years later, King would extrapolate on these ideas with Vera Smith, whose fanaticism becomes extremism. These darker visions of religion in King's early books are tempered by the positive power of religious iconography such as crosses and holy water (as well as Father Callahan's desire to return to a less modern understanding of Catholicism) in 'Salem's Lot, and of course King's epic story of good versus evil in The Stand, in which Mother Abigail is cast in the role of Moses, leading her people to salvation.

More minor instances crop up in the interim: while not specifically religious, Pet Sematary's use of names like “Church” and “Creed” are evocative. Cycle of the Werewolf perversely casts a priest in the role of the monster. Annie Wilkes quotes Bible passages in Misery. In It, King suggests that a force greater than either It or the Turtle is on the Losers' side; obliquely referencing God, King refers only to the force as the Other.

1991 marked a return to a more specific look at God, and King's interest in religion as a narrative conflict. Starting with a subplot focusing on religious violence in Needful Things, King began to explore these concepts more in depth. The Green Mile features John Coffey as an analogue to Jesus Christ (his initials only the most blatant clue to the comparison). Later, Storm of the Century and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon would both tackle variations on these ideas (while “That Feeling, You Can Only Say What It Is In French” would explore an interpretation of Hell). Just as King's early 90s work concentrated on women's issues, these later books create a loose series of works revolving around God, religion, and the consequences of belief.

Central to this series is Desperation, King's most pointed look at God. Cleverly, King injects references to religion in subtle, often secular ways throughout the novel's early pages, as if preparing readers emotionally for the focus of the book later. Interestingly, the novel's first sentence:

“Oh! Oh Jesus! Gross!”

takes the Lord's name in vain. Similarly, Johnny Marinville – one of King's many writers, and one of the central characters of Desperation – spouts nonsense preacher doggerel while urinating. It's not as if these characters are particularly anti-religion, it's just that it doesn't figure largely in their lives.

Enter David Carver, a boy who has a special relationship with God. A year earlier, he made his first prayer, entering into a pact with God to save his critically injured best friend in exchange for later service. In the year since his friend's miraculous recovery, David has studied the Bible and prayed, trying to understand the nature of God; the decision Desperation comes to over and over is that “God is cruel.” The events of Desperation reinforce this mantra: coming home from a vacation in Nevada, David and his family are pulled over by an immense police officer named Entragian, who tricks them into town and then murders David's little sister.

The truth of Entragian is darker: he is possessed of a demonic force known as Tak, who exists (in some fashion) at the heart of a reopened copper mine in the center of town. The imprecise nature of Tak is important. King suggests that Tak might be the literal Devil (going so far as to name the mining company that disturbed Tak's prison Diablo, meaning devil in Spanish) and that Tak exists in Hell. But suggestions and sketches are all King allows, unwilling to define Hell in literal terms. This is to the book's credit. Generally, the less we know about King's villains, the more frightening they are. Witness Randall Flagg's murky origins, or the barely-sketched beginnings of Barlow the vampire in 'Salem's Lot or Needful Things' Leland Gaunt. Conversely, the final manifestation of It as a spider – a familiar image that, despite its cosmic implications, somewhat undercuts the basic horror of it.

Tak's defining characteristic is that it must work through people in order to exist physically in our world. After possessing Entragian, Tak then takes control of David Carver's mother, destroying her in the process. David's God, likewise, must also work through people to carry out his work; the crucial difference is that God's possession is spiritual, not physical, allowing for free will (a concern introduced in The Green Mile that would later recur in Storm of the Century).

David understands these things, even when he doesn't agree with them. King is very careful to make David's piety very human, making him consistently relatable. Though he is something of a prophet and can perform miracles (a particularly clever scene involving sardines and crackers recalls the miracle of Jesus' feeding the multitude in Gospels), David remains a young, scared boy whose powers are greater than he. In this context, Desperation fits in with King's early sequence of books featuring young protagonists and their “wild talents,” chief among them Carrie, The Shining, Firestarter, and It. That King is willing to revisit this type of character is interesting, given his conscious decision to move away from the “children and monsters” themes that defined much of his early work.

In some ways, though, Desperation serves as the same sort of bridge as It, connecting early and latter interests. One of Desperation's most important characters is Johnny Marinville, a novelist whose self-destructive behavior grows as important to Desperation's narrative as its religious undertones and more visceral horrors. Johnny continues the thread of writers at crucial points in their careers, starting with Misery and continuing into later work such as Bag of Bones and Lisey's Story. Importantly, Johnny's character revolves less around his writing than his fundamental lack of self-worth. Here, Johnny echoes Jack Torrance of The Shining, and his symbolic father/son relationship with David further recalls that of Jack and Danny. While Jack's internal issues stem from a childhood of abuse, Johnny's come from the horrors he had witnessed in Vietnam (a theme King would explore in much greater detail in the later Hearts in Atlantis). Slowly, Desperation emerges as Johnny's story, with the struggle to regain his soul the crux of the novel.

The introduction of God and religion as narrative forces is intriguing. The persuasive, straightforward narrative does not equivocate on the subject of religion, much as prior books do not equivocate on the paranormal or supernatural; King simply asserts, and the reader chooses whether to accept. Religious metaphor and iconography are prevalent throughout the novel; David's role as Job is one of Desperation's defining themes: after the murder of his sister and possession of his mother, his father, Ralph, is torn apart by Tak. In two important sequences, David symbolically takes the Eucharist (here represented by 3 Musketeers wrapper). False idols become an unlikely source of horror, as Tak's can tahs and can taks reveal people's baser natures and devolve them into dangerous, obsessive behavior (an effect similar to that of Maerlyn's Grapefruit in Wizard & Glass, and to some extent Christine herself). Names, always important to King's work, are here often Biblical: Mary, Steven, John, Thomas, and especially David. While the Biblical David slew the giant Goliath after King Saul allows him to attempt it, in Desperation, Johnny takes David's place in the final stand against Tak.

Despite Desperation's focus on the nature of God and religion, it remains eminently approachable to secular readers. Beyond its deeper concerns, Desperation is also one of King's most effective horror novels. Spiders, snakes, and coyotes are all deadly sources of horror, as is the initial presence of Entragian the police officer (recalling earlier murderous policemen like Frank Dodd in The Dead Zone and the more recent Norman Daniels in Rose Madder).

Desperation's primary asset is in revisiting many of King's earlier themes and combining them in new ways. Compared with The Regulators (the Richard Bachman novel with which it was released concurrently) it seems even more important, resonating deeper and making more profound statements than its more violent companion. While perhaps not as vital to King's greater canon as The Green Mile – a novel whose religious motifs anticipate those of Desperation, albeit more subtly – Desperation remains a solid, serious book, one of King's most powerful novel-length works.